Designing the Spotify perimeter

In this blog post we focus on the web load balancers and various proxy systems across the Spotify perimeter. We go through the ways we expose our service network to the Internet and the challenges we faced while automating that.

Team autonomy is a big part of the Spotify culture and in this blog post we will cover the processes that allow our developers to get bidirectional internet access through perimeter in an easy and secure way without any SRE assistance.

One year ago…

The Spotify perimeter did not really exist. A good network perimeter can be thought of as a robust wall that keeps intruders out and protects the inside. A year ago our perimeter could be thought of as less of a wall and more like a makeshift barrier put together with duct tape and glue. No single person in the company knew all the IP ranges Spotify was using or in what way backend systems were exposed directly to the Internet. It was a security and operational nightmare and we made it a priority to improve the situation.

© Lynn Friedman @flickr

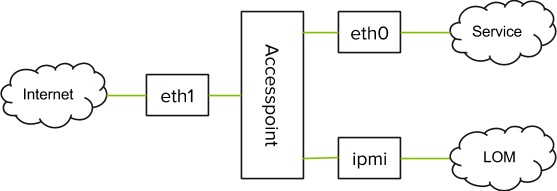

A year ago Spotify had around 7,000 servers in the production network running more than 100 different services. Among these were a plethora of legacy machines that no one remembered, many of which were accessible directly from the Internet. Even though most servers were behind firewalls, all the machines had public IP addresses and could talk to the internet. Even IPMI interfaces had public IP addresses back then, and we were wasting the scarce IPv4 ranges.

At the time we were providing two ways to expose machines to the internet: developers could ask our network team to create a firewall rule that would allow incoming connections or they could ask the datacenter team to patch a cable with an un-firewalled switch port to a separate interface of the server. Both methods were time-consuming, required manual work and did not scale well.

Designing the perimeter

We decided that something needed to change. After a thorough assessment of the situation we realized that we could move most of the backend systems behind a small set of well defined perimeter hosts.

Having only perimeter hosts talking to the Internet would make life easier for the service owners. For starters, developers would not need to care about firewalls or network cables which would eliminate some security risks. Additionally, we would be able to use private IP ranges for all the backend services and we could implement the perimeter self-service by exposing configuration our developers could change, eliminating the need for them to interact with the network or data center teams in order to make changes. On top of that, we would be able to provide some standard features such as event delivery, logging, and security audit with no additional effort from the service owners.

Setting our goals

Of course, all the perimeter systems would need to be rock solid to achieve this objective. They would need to be highly available and horizontally scalable. The configuration would need to be very easy to use and secure by default so that developers would not need to have an in-depth understanding of our security practices in order to use the service. Furthermore, all the traffic going through the perimeter would need to leave an audit trail in the event we would need to inspect activity at a later date.

We would also need our perimeter systems to work both in our data centers and in the various cloud environments provided by external partners. That meant that we could not depend only on our own on physical network infrastructure.

Perimeter systems

To find solution that could meet all the requirements listed above was not a trivial task. Fortunately, most of our backend services have fairly generic use cases, so we’re able to cover all of these with just a small set of perimeter systems. This text will focus on the perimeter systems that are built with open source technologies: web load balancers, incoming TCP proxy, single-sign-on (SSO) proxy and outbound proxy.

Web load balancers

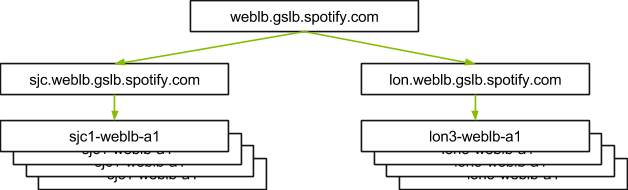

One of the primary use cases for the Spotify perimeter is to enable incoming access to HTTP based services. We are using dyn.com to solve 2 problems: how to direct our clients to the pool of the load balancers in the closest datacenter and how to remove dead servers based on health checks from different locations.

We are using standard nginx server on the load balancers. Having DNS failover with simple health checks to achieve high availability is not without its faults. Slow health checks can for example lead to long recovery times, but it’s a simple solution that works everywhere and meets our SLA. Thus far we have been very happy with it.

Dealing with multi-tenancy

We decided to split load balancers in 3 clusters to handle different kinds of requests. First, we have a generic pool for our standard websites, such as www.spotify.com or partners.spotify.com. Requests to these websites are generated by web browsers and served only from 2 locations: Europe and the West Coast of the US.

The second cluster is serving API endpoints and handles requests from the Spotify application and other smart clients. Those clients usually have some logic to handle retries and are much more sensitive to latency. Load balancers in this cluster are located in every datacenter to keep up with the high volume of requests that they handle.

Finally, we have a cluster that serves payment-related traffic. Payment systems have a different SLA and are more sensitive to the information they log and store. We also must notify our partners when we extend or change this cluster because they often have strict firewall restrictions and need to whitelist all the IP addresses used by the load balancers.

Overall, we have around 50 services behind web load balancers.

Configuration and commit to deploy

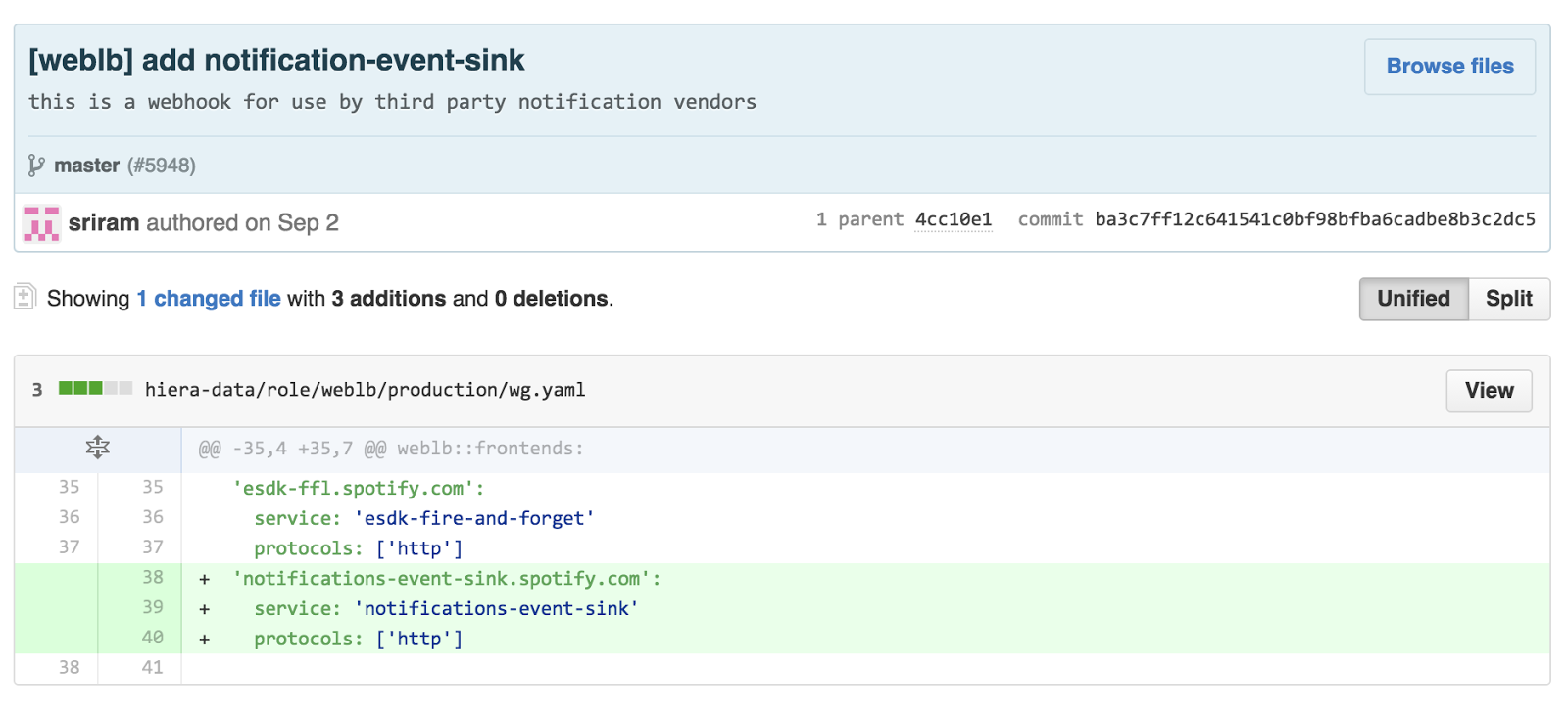

At Spotify we use Puppet to configure almost everything, and load balancers are no exception. We introduced a simple syntax that allows you to add a new website using just 2 lines of yaml tree in hiera.

Only the website name and service discovery name are required to configure a new website, and changes can be submitted in a self service manner without involving SRE. All the developer need to do is to make sure that the change passes all tests and get a review from a colleague. We run puppet every minute on the load balancers, so all the configuration and topology changes are applied almost instantly.

Keeping it simple

We have decided not to implement application or business logic features on top of the load balancers to keep it simple, generic and uncluttered. This has the benefit of making it easier to switch to a different setup should we need to. Functionality such as rewrite rules or rate limiting is kept in the backend.

Having said that, we do provide geolocation headers with country codes and AS numbers since it’s much easier to handle updates of the MaxMind database in one place. Load balancers also ship logs to our Kafka, Hadoop and ElasticSearch clusters. Among other things, this setup provides near real-time visualization of all incoming HTTP requests across the entire perimeter.

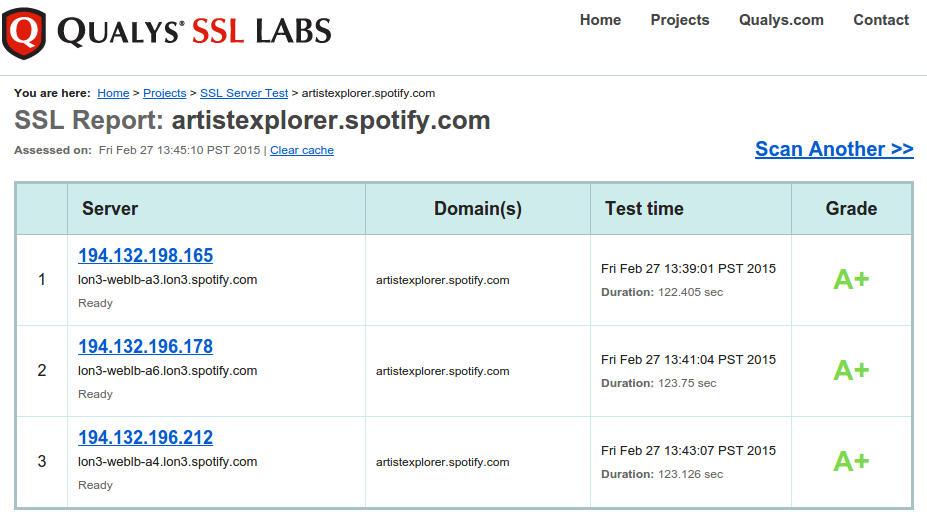

We also try make the websites secure by default. Developers do not have to understand what HSTS is, which SSL certificates to use or how to update openssl: they get all of this for free with just two lines of configuration. This makes our security team happy because they have an easy way to discover and audit all the public websites we have.

Health checks

Nginx does not support active health checks in the OSS version. Instead, it tracks backend liveness by looking at the responses and removes servers from rotation based on the proxy_next_upstream directive. By default, proxy_next_upstream equals “error timeout”, which means that if an upstream can’t process a single HTTP request in time for some reason, it will be removed from the rotation for 10 seconds (default fail_timeout).

Coupled with retries, nginx could in theory remove all the servers from rotation, retrying the same slow request to each upstream. This could cause an outage rather quickly, especially if some locking mechanism is used, or if a backend depends on synchronous requests to a third party. In general, retries are not safe since HTTP requests are often not idempotent, and nginx retries both GET and POST requests by default. That pushed us to switch to active health checks.

We had a choice between using a third party nginx module or setting up HAProxy behind nginx on every load balancer. We went with HAProxy because it’s much easier to maintain and has a reputation for being a very stable load balancer.

Sometimes we get asked: why not just use HAProxy without nginx? First, nginx supports geolocation via databases provided by MaxMind, a feature which is used by many websites at Spotify. Second, it has a more mature SSL termination: configuring SSL stapling, for example, is much easier. Finally, nginx supports file-based logging. We had a few issues in the past with syslog being CPU-bound on the log-intensive systems and we want to avoid this problem.

Incoming TCP proxy

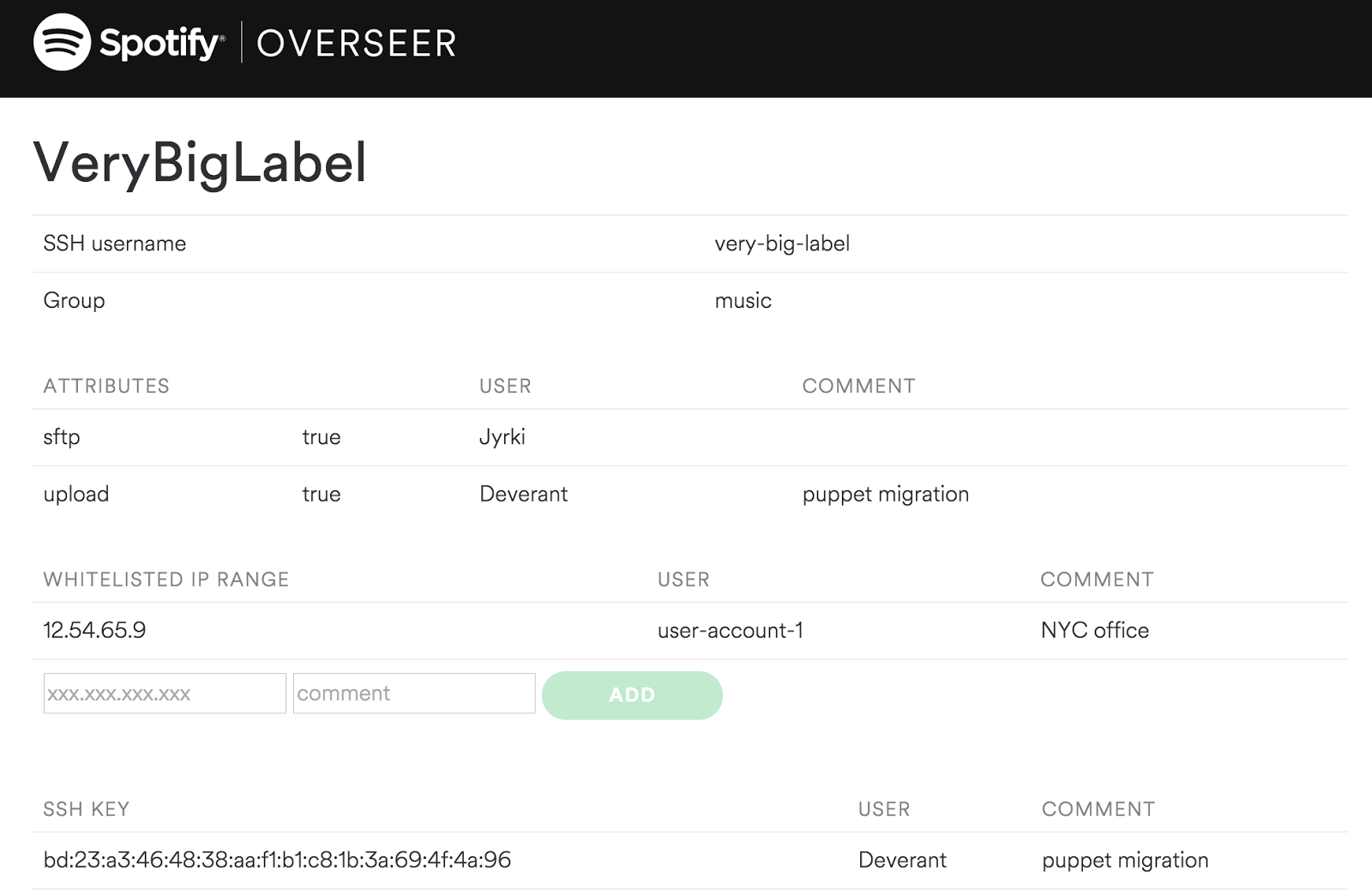

Inbound proxy is similar to the web load balancers: we use dyn.com to direct clients to the closest datacenters and HAProxy on the servers to handle incoming TCP connections. Today we have just 2 clusters that receive music and video content from various organisations that provide our content. The files get uploaded using SFTP and are stored on a network file system which is mounted on the backends behind HAProxy.

Security requirements on the inbound systems are strict, and we have to block non-whitelisted IP addresses from establishing connections. We are working with quite a few such organisations and at some point keeping a comprehensive list of the IP addresses in hiera did not scale anymore. To solve this problem, our content team moved out the firewall configuration to a separate database with a simple frontend and integrated it with puppet using the firewall module.

Internal SSO proxy

We use Shibboleth as our single sign-on mechanism for employees. The system consists of 2 parts: an identity provider and a reverse-proxy for the internal websites. When users open an internal website for the first time they connect to the SSO proxy first and then get redirected to the IDP which handles authentication.

We had to write our own login handler in order to support our 2 authentication mechanisms: YubiKey and Google Authenticator.

Configuration: all the same

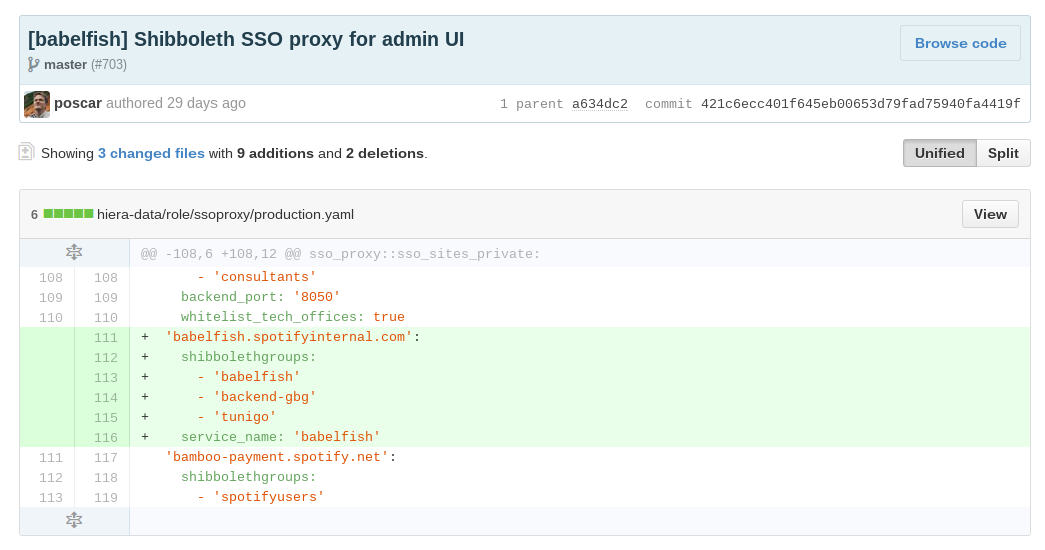

Single-sign-on (SSO) proxy and web load balancers are configured in the same way: developers need to add a couple of lines to the puppet configuration and merge the changes themselves. Additionally, with SSO proxy it’s possible to specify LDAP groups that can access a particular internal website or disable authentication from specific subnets or from internal systems.

Adding a new website does not require DNS changes since we have a separate domain with a wildcard CNAME for our internal websites. Since SSO proxy works transparently, no changes need to be made to the websites, even if they are serving static html pages.

External service providers

We have more than 200 websites behind SSO proxy, and as such it’s important the system is completely automated. Unfortunately it unfeasible to automate this setup with external websites that need to be authenticated via SSO. Each third-party service provider needs to be added manually, and it usually takes quite a lot of time and e-mails to get that done.

To make matters worse, it does not look like there is an alternative: most of our external resources only support SAML so switching to Google OAuth2 may not be an option.

Outbound proxy

The outbound proxy is by far the most used part of the perimeter: a lot of backend systems need to talk to the Internet. When we designed this part of the perimeter, we had some serious limitations:

We don’t have access to enough public IPv4 addresses to cover all our current servers and planned expansion

Audit trails were required for all outgoing connections

The system needed to work both in the cloud and in our physical datacenters

It also needed to be homogeneous, scalable and highly available

There is no nice, easy or elegant solution to this problem, and we decided to go with the simplest one we could think of.

Every datacenter has a cluster of Squid boxes, and every host has a HAProxy instance that load-balances connections between them. When an application makes an external connection, it gets redirected by iptables to redsocks which then wraps the connection with CONNECT proxy command and sends it to the local HAProxy.

We are using Squid to peek and splice SSL connections in order to have better audit trail, with domain names extracted from SNI. All the information gets logged and shipped to our Kafka, Hadoop and ElasticSearch clusters.

Everything works transparently, and no additional configuration is required from the backend systems.

Environment variables

We ended up with our current setup after some experimentation. One of the failed experiments was to use the http_proxy environment variables and skip the transparent proxy setup. It turns out that there is no reliable way to set up system-wide environment variables in Ubuntu; a lot of applications and frameworks have poor support for http proxy or have bugs in environment parsing. Also, there is no way to exclude IP ranges with no_proxy variable, and some internal traffic would end up going through the proxy. The only reasonable way forward was to switch to using a transparent proxy.

SSL Bump

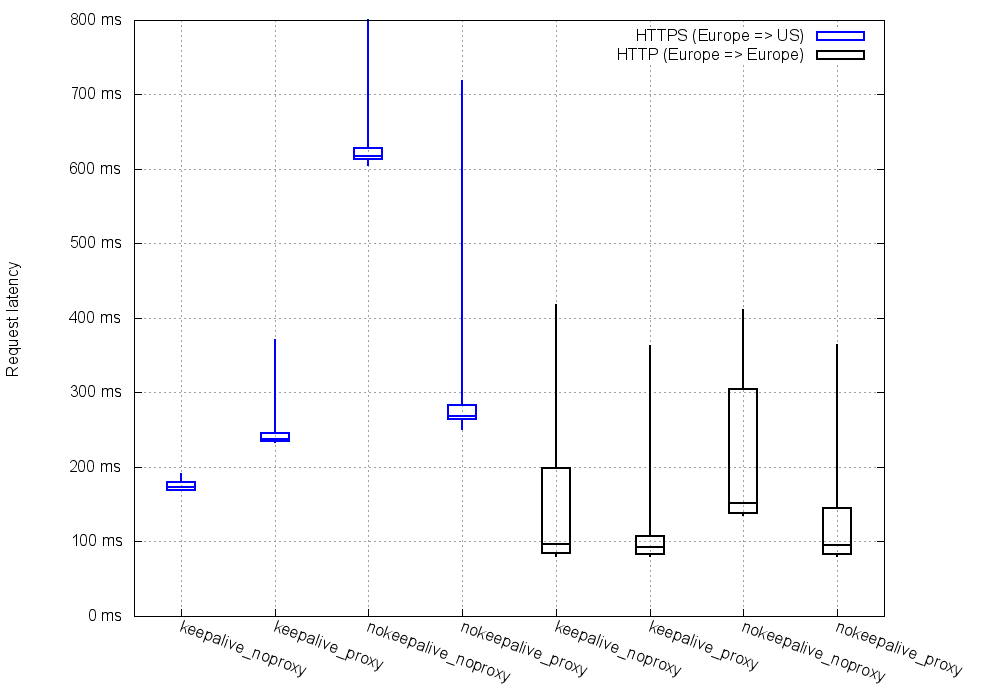

Another failed experiment was to use SSL Bump to inspect outgoing HTTPS connections. We managed to roll out our own SSL certificate across all of our backend systems, but with wider deployment it became clear that we had a lot of problems with bundled CA certificates. Our developers were having too many issues with various libraries and spending time to solve them would take too much time. Also, peek-and-splice is a relatively new feature in Squid, and it’s not very stable yet. We were a bit disappointed to disable SSL Bump because it would have allowed us to reuse HTTPS connections between applications and significantly improve latency.

For simple clients that do not use keepalive, SSL Bump was saving around 300ms for each cross-Atlantic HTTPS connection.

Reaching our goals

Spotify has grown big enough that it became fairly complicated to change the underlying backend topology. A lot of our teams and external partners had to collaborate on the perimeter effort. It took quite some time and caused a few incidents, but in the end we have accomplished the goals we set up. We provide our teams with tools which make their services more available, scalable and secure. In the end, we are happy with the results and hope that our experience and the things we learned along the way can inspire organisations with similar challenges.