To Coach or Not to Coach?

A little while back during a coaching book club, a few Spotify coaches started a discussion about a common pitfall they found: why do we default to the coaching stance so much? The coaching stance is a tool used to help a partner to think and problem solve a situation through non-judgmental dialogue with the coach. It typically looks like a conversation with lots of open ended questions asked by the coach that provoke thought and contemplation in the partner. It’s a powerful tool, and when it works, it tends to work very well, which is part of why it’s a kind of default go to when approaching a coaching situation.

We all know the classical wisdom that it’s far better to teach a woman to fish than to just give her some fish, so why is defaulting to the coaching stance not the best thing to do? Because, at the time of the coaching conversation, your partner may lack the knowledge, skills or emotional resources to effectively solve the problem at hand. In example, your partner may be defensive and not want to have dialogue at all. She may be too stressed out to follow through with her own thinking. She may resent the coaching approach in that context and find it to be patronizing. She may just want an answer and is not interested in learning at that particular moment in time. She may even lack some foundational knowledge to be able to work through the problem. Maybe your partner is just famished, and she just needs a fish to eat, before she can be ready to learn how to fish by herself.

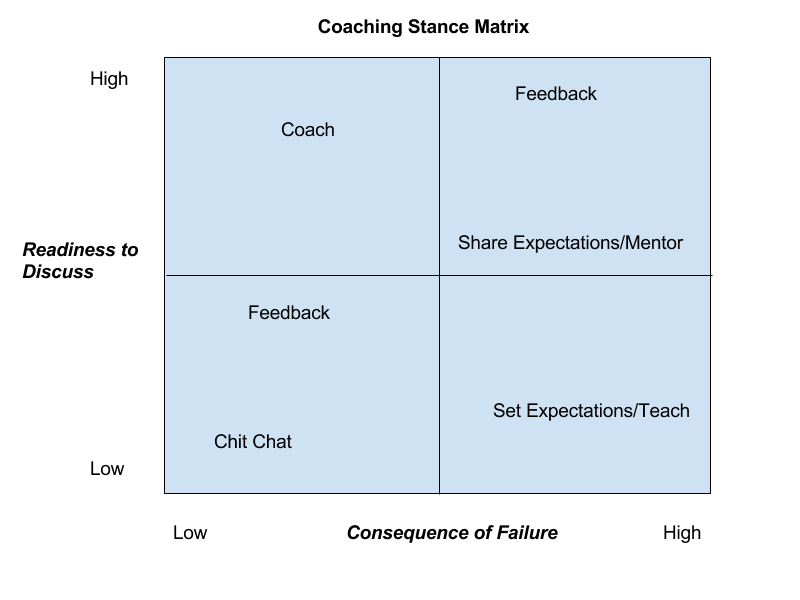

So, how do you know when to choose the coaching stance versus any other stance like mentoring or teaching or setting expectations? That’s the debate that spun off from that book club discussion, and this debate led to a visual model and a bit of a blurb about it that you can see below:

The model crudely tries to capture a lot of components that were exposed in the discussion. The main gist is that when approaching a coaching situation whether it’s with an individual or a team the coach should check in with themselves on the two dimensions at play for that particular situation: how ready is your partner to actually be coached and how much risk is there if they make the wrong choice.

The consequence of failure is a measure of the negative impact that could occur in this situation from a poor choice or action. Suppose a team lead comes over to you and tells you they have to decide if to let go of someone or not by tomorrow. This decision carries considerable weight to it. Someone might lose their job. The company could potentially be at some kind of legal risk. And, the team could suffer. Getting this decision wrong could be quite costly. So, what happens if you coach them for an hour and the team lead comes up with an option you know is not good? They could walk away and do the wrong thing at considerable cost. On the other hand, if the team lead comes over to you and asks you to help her figure out how to improve her backlog grooming sessions, then what’s the risk of her choosing an ineffective approach? Probably not much. You can probably try something else next time. So, the consequence of failure at this particular instance is typically low. If we generalize this rule of thumb, we can say that the consequence of failure is the combination of how many chances you get to get it right and how damaging it would be to get this one choice wrong.

Readiness to discuss is about what approach has a good chance of helping in your current situation. In general, it tries to capture the circumstances of the interaction at the time when the conversation needs to take place. These circumstances include your current mindset, your partner’s stress level, the level of maturity that your partner has for discussing the topic at hand, the nature of your relationship with this partner and so on. Because it’s a more complex concept, it is one that often requires experience to be able to gauge how ready both you and your partner are at the moment the conversation takes place.

We can start by observing our partner. It’s useful to think about the maturity of the person or team in front of you. How effective would coaching be for a team of developers that has just formed and has never worked in an agile fashion? Probably not very. What they typically need is to be taught and exposed to a tool they’ve never heard of before (like post mortems or user stories). You might want to think about your team in terms of Tuckman’s model in order to assess what they need at this point. And when it’s about an individual, the same attitude applies. Are they new to the role or the company? Do they have the kind of foundation at what they have been doing that allows them to think about the problem at hand, or do they need more pieces to complete this puzzle? Sometimes, it’s important for us as coaches to recognize that we have very useful and valid knowledge and experience that weshould share regardless of what stance we choose.

We may also want to take stock of our relationship with our partner. Does your partner have a dependency on you or your advice? Are they coming to you for suggestions or ideas frequently? Are they getting better at solving their own problems? Maybe the last three times you’ve spoken you’ve opted to teach, and now it’s time to coach a little, so they can maybe learn to work through this challenge? Similarly, you ask yourself how often are you pushing your ideas onto them versus pulling their thoughts? Maybe you check in with yourself and realize you’ve been too pushy lately. Ok, try pulling. Coach a little. Maybe it’s the other way around, and it’s a good time to just offer a suggestion. There are many other aspects one can think about, but these are good places to start with.

There’s also the emotional and intuitive aspects of assessing the situation. Have you ever sat in front of someone and had that frustrating sense that they are trying to coach you? As one coach here said: “if you have something to say, say it.” This kind of gut sense is important for a coach to go through. If you know you want to go to a particular thought or destination you have, then offer it up, and then pull for their thoughts. For example, “I noticed you often take too much space during facilitation. I think it’d be good for the team if you were able to hold silence for longer, so the introverted folks could talk. What do you think about that?” Notice that pulling, open ended question at the end? That’s not the coaching stance. That’s working together with someone to further along their development with strong beliefs, lightly held.

It’s useful to consider your partner’s emotional state. If you can see that they are nervous or anxious, then probably asking them to think through a coaching session isn’t the best option. Maybe they need more support and mentoring to help them through that day. Same goes for a team that is under a lot of delivery pressure. Would you want them to figure out how to improve some aspect of their process now? Or, do you first help them put out the fire, deliver, and then hold a retrospective where you can coach them into learning how to do better next time? Also check to see how you’re currently feeling. Are you able to hold the space required for a coaching session? Maybe you are too stressed out, and now is really not a good time for you. That’s important too. You can offer to postpone the coaching session, chit chat, or be more assertive with teaching or setting expectations — all depending on the urgency of the situation. Overall, you want to be sure that everyone involved in a coaching conversation is in the right emotional space for it.

When you put all of this together, you can see how defaulting to the coaching stance isn’t always the best option. It’s probably best to start by evaluating how urgent the situation is by looking at the consequences of failure, because these consequences are typically driven by external conditions that we have no control over. Once you’ve figured that part out, you can check in to see what kind of conversation you and your partner are ready to have right now. And, once you got the sense of those two dimensions, you can pick your stance and go with it. And remember, sometimes you want to teach a woman to fish, and sometimes, it’s best to share what you have.