Spotify’s Love/Hate Relationship with DNS

Forward: This blog post accompanies our presentation given at SRECon 2017 in San Francisco. The recording of the talk can be viewed here, with the accompanying slides here.Spotify has a history of loving “boring” technologies. It’s not that often people talk about DNS; when they do, it’s usually to complain, or when a major outage happens. Otherwise, DNS is initially set up – probably with a 3rd party provider – and then mostly forgotten about. But it’s because DNS is boring that we love it so much. It provides us with a stable and widely-known query interface, free caching, and service discovery.

This post will walk through how we have designed and currently manage our own DNS infrastructure, our curious ways in which we use DNS, and the future of the lovably boring technology at Spotify.

Our infrastructure

We run our own DNS infrastructure on-premise which might seem a bit unusual lately. We have a typical setup with what we call a single “stealth primary” (and a hot standby) running BIND, and its only job is essentially to compile zone files. We then have a bunch of authoritative nameservers (or “secondaries”), also running BIND, with at least two per geographical location, and four of which are exposed to the public. When the stealth primary has finished re-compiling zones, a transfer happens to the nameservers.

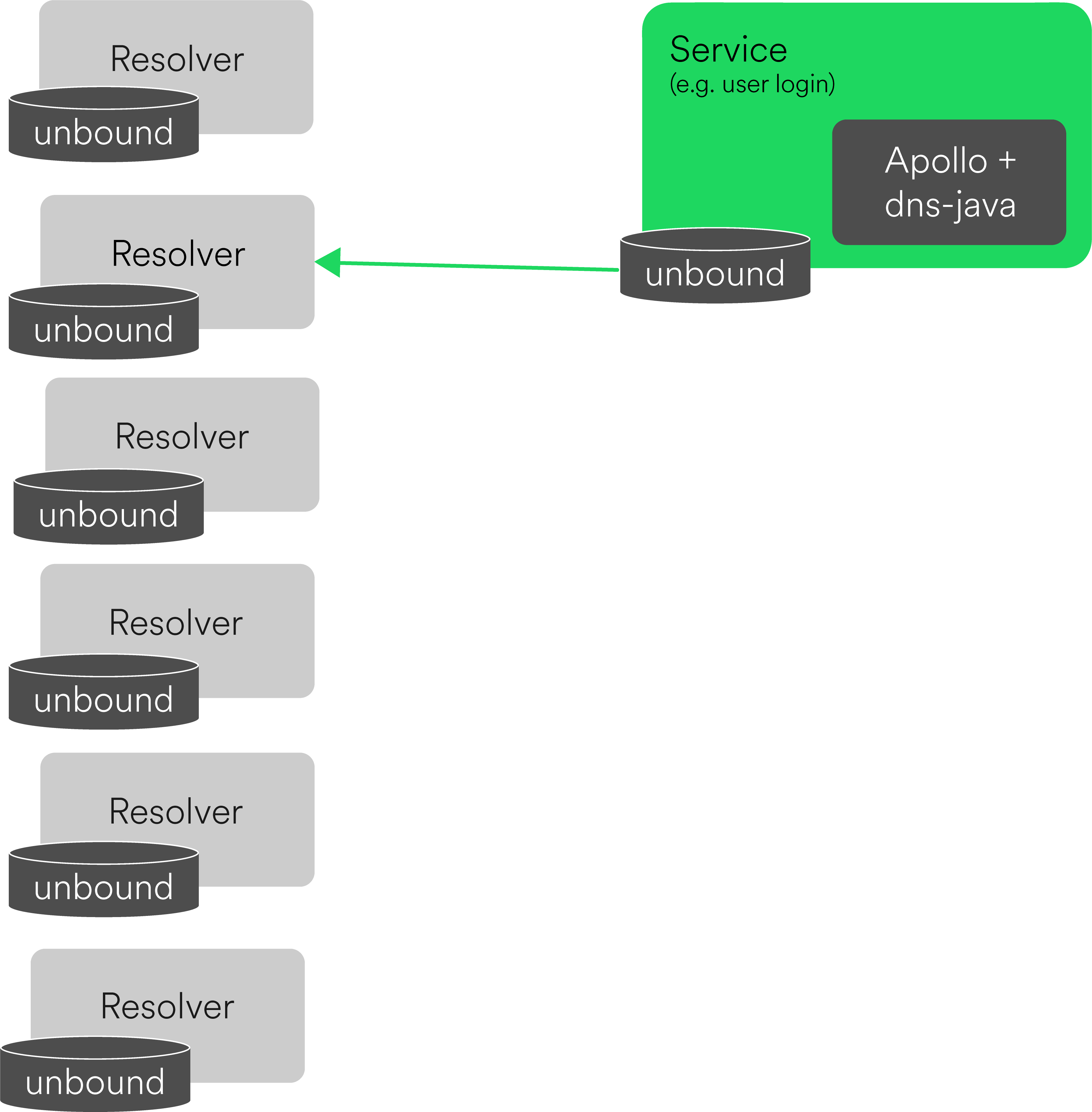

We then have a bunch more resolvers running Unbound (caching and recursive DNS server software), with at least 2 resolvers per datacenter suite. Our resolvers are configured to talk to every one of our authoritative nameservers for redundancy.

We also have Unbound running on each deployed service host, configured to use the resolvers in the service’s site. Using Unbound everywhere gives us the caching that we’d rather not implement ourselves. We have also always relied on DNS for service discovery, so Unbound helps avoid many requests from individual services that can effectively DDoS ourselves.

The Unbound service randomly selects its DNS server to send queries to based on a round-trip time (RTT) band of less than 400 milliseconds. This unfortunately does not mean that Unbound will always select the fastest-responding server. However, as you can see from the output below, from one of our resolvers located in Google Compute’s Asia East region (to which the gae prefixed in the hostname refers), the fastest responding authoritative nameserver is logically located in the same region. The others under the 400 millisecond threshold are located in the physically closest region, western US; then every other nameserver has a RTT higher than the 400 millisecond band.

root@gae2-dnsresolver-a-0319:~# unbound-control lookup spotify.net

The following name servers are used for lookup of spotify.net.

The noprime stub servers are used:

Delegation with 0 names, of which 0 can be examined to query further addresses.

It provides 18 IP addresses.

10.173.0.4 rto 706 msec, ttl 309, ping 62 var 161 rtt 706, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.173.0.5 rto 706 msec, ttl 236, ping 62 var 161 rtt 706, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.174.0.6 rto 548 msec, ttl 251, ping 68 var 120 rtt 548, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.174.0.25 rto 500 msec, ttl 246, ping 36 var 116 rtt 500, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

23.92.97.20 rto 603 msec, ttl 249, ping 63 var 135 rtt 603, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

23.92.102.148 rto 565 msec, ttl 238, ping 45 var 130 rtt 565, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

78.31.11.120 rto 738 msec, ttl 248, ping 82 var 164 rtt 738, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

194.132.176.115 rto 738 msec, ttl 299, ping 82 var 164 rtt 738, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.254.35.16 rto 743 msec, ttl 238, ping 83 var 165 rtt 743, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.243.97.245 rto 742 msec, ttl 243, ping 82 var 165 rtt 742, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

194.71.232.219 rto 729 msec, ttl 246, ping 65 var 166 rtt 729, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

193.181.6.79 rto 734 msec, ttl 246, ping 66 var 167 rtt 734, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

193.181.182.199 rto 803 msec, ttl 247, ping 91 var 178 rtt 803, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

194.68.177.51 rto 154 msec, ttl 241, ping 134 var 5 rtt 154, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

194.68.177.243 rto 150 msec, ttl 302, ping 130 var 5 rtt 150, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.163.6.191 rto 649 msec, ttl 350, ping 41 var 152 rtt 649, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.175.0.4 rto 12 msec, ttl 306, ping 0 var 3 rtt 50, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

10.163.216.81 rto 811 msec, ttl 244, ping 75 var 184 rtt 811, tA 0, tAAAA 0, tother 0, EDNS 0 probed.

In addition to running Unbound on each service host, the services of which are built using Apollo, our open-sourced microservice framework in Java, also makes use of dns-java, providing us with another layer of resiliency. The dns-java library will hold onto cached records for an hour if the local Unbound service fails or our DNS resolvers aren’t responding.

DNS record generation & deployments

Like many tech companies, we’ve grown into better practices. We did not always have the setup of automatic DNS record generation and deployments that did not require babysitting and forewarning.

Before the push to automating DNS deploys and zone data generation, we hand-edited our zone files, committed them into version control (fun fact: we started with Subversion then moved to Git around 2012), and then manually deployed the new zone data with a script ran on our primary.

08:35 < j***k> and also VERY FUNNY PEOPLE

08:35 < m***k> j***k likes us \o/

08:35 < s***k> we like j***k

08:36 < d***n> DNS DEPLOY

08:36 < j***v> What is this "DNS DEPLOY" thingy you guys keep screaming?

08:36 < d***n> j***v, when we deploy new dns content

08:36 < j***k> http://i.qkme.me/364h55.jpg

08:36 < j***v> Alearting eachother?

08:36 < d***n> yup

08:37 < j***v> d***n: Why?

08:37 < d***n> in case there's problems and I guess also as a locking mechanism ?

After feeling too much pain with manual edits and deployments, in 2013 we made the push for automation. We started first with making incremental pushes to script our record generation. Then we added required peer reviews and integration testing for records that still needed manual edits (e.g. marketing-friendly CNAMEs). Finally in 2014, we were comfortable enough to “forget” about DNS after setting up cron jobs for regular record generation and DNS deploys.

Our automation in detail

We have a pair of cron’ed scripts written in Python that are scheduled to run every 10 minutes (staggered from each other): one script generates records from our physical fleet via a service of ours called “ServerDB”; the other script talks to the Google Compute API for our cloud instances with deployed services.

That script takes about 4 minutes to get lists of instances for every service, and finally commit to our DNS data repository, which we consider our source of truth.

We then have another cron that will run about 3 minutes after the git push. The stealth primary hosts this cron job, which runs every 5 minutes. It simply pulls from our DNS data repository, then compiles all the zone data via named. With every compile time – which takes about 4 minutes – we update a particular TXT record that reflects the git commit hash that’s currently being deployed to production.

Once done, the primary notifies our authoritative nameservers of potential changes to the newly compiled zone files. The authoritative nameservers then query the primary to see if there are any zone changes, and if so, initiates an authoritative transfer (AXFR). These transfers to the nameservers also take about 4 minutes.

Looking at the timeline in the animated diagram above, it takes – at best – 15 minutes for the record of a new service’s host or instance to propagate.

What about Service Discovery?

SRV records had also been hand-crafted. This, however, became problematic. Typically, changes to DNS are relatively slow, but service discovery needs to move fast. Couple that with manual edits being prone to human error, we needed a better solution.

Earlier in the infrastructure overview, we have services locally running Unbound, talking to our resolvers:

Since the then-current open source solutions did not address all of our needs, we built our own service discovery system called Nameless, supporting both SRV and A record lookups. It allows engineers to dynamically register and discover services, which made it easier to increase and decrease the number of instances of a particular service.

To separate service discovery from regular internal DNS requests, Nameless owns the services subdomain, e.g. services.ash2.spotify.net.

$ spnameless -b lon6 query --service metadata | head -n 4

query: service:metadata, protocol:hm (75 endpoints)

lon6-metadataproxy-a1142.lon6.spotify.net.:4620 (UP since 2017-03-11 00:58:07, expires TIMED)

lon6-metadataproxy-a1168.lon6.spotify.net.:4620 (UP since 2017-03-11 00:58:18, expires TIMED)

Monitoring

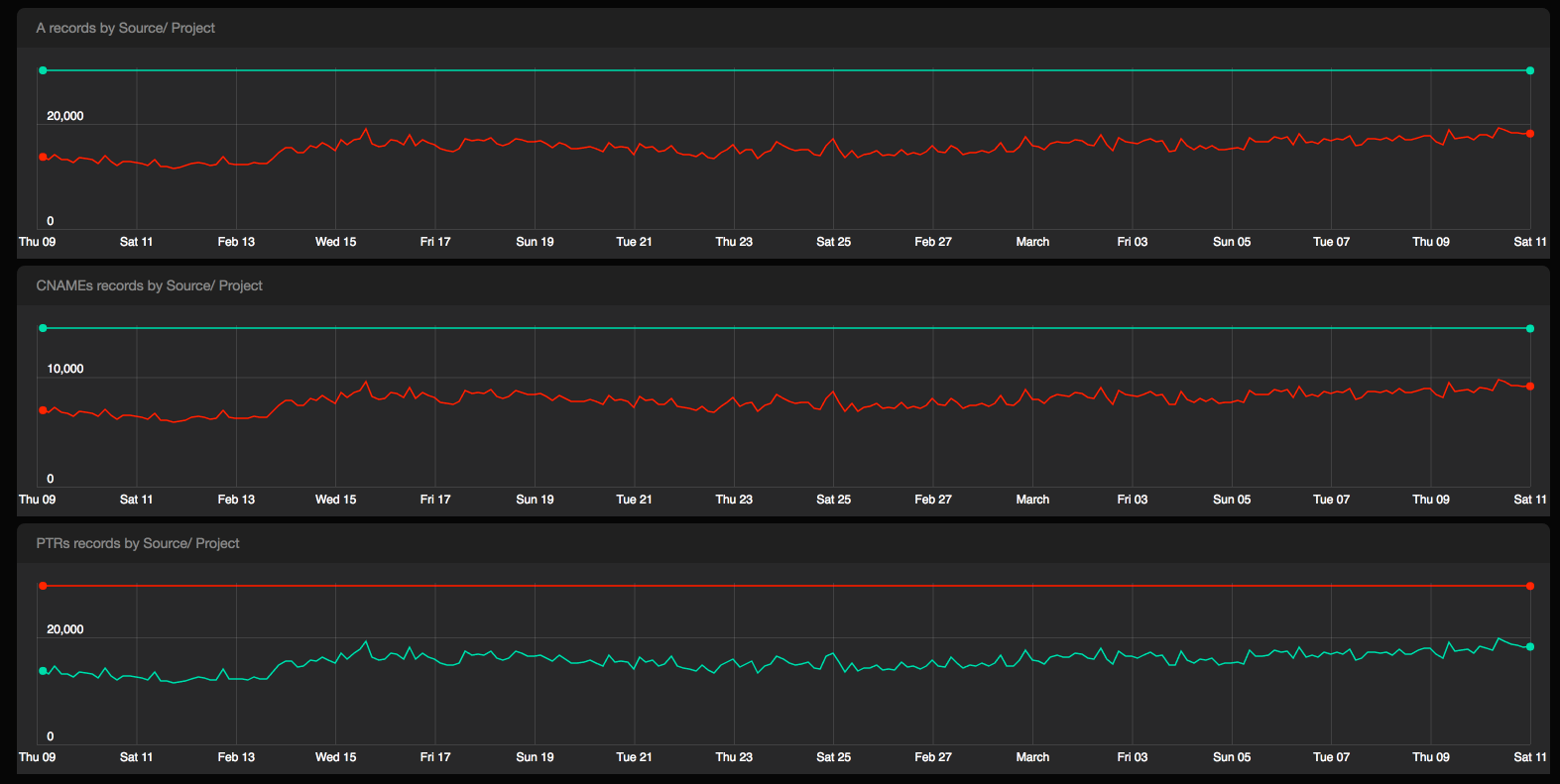

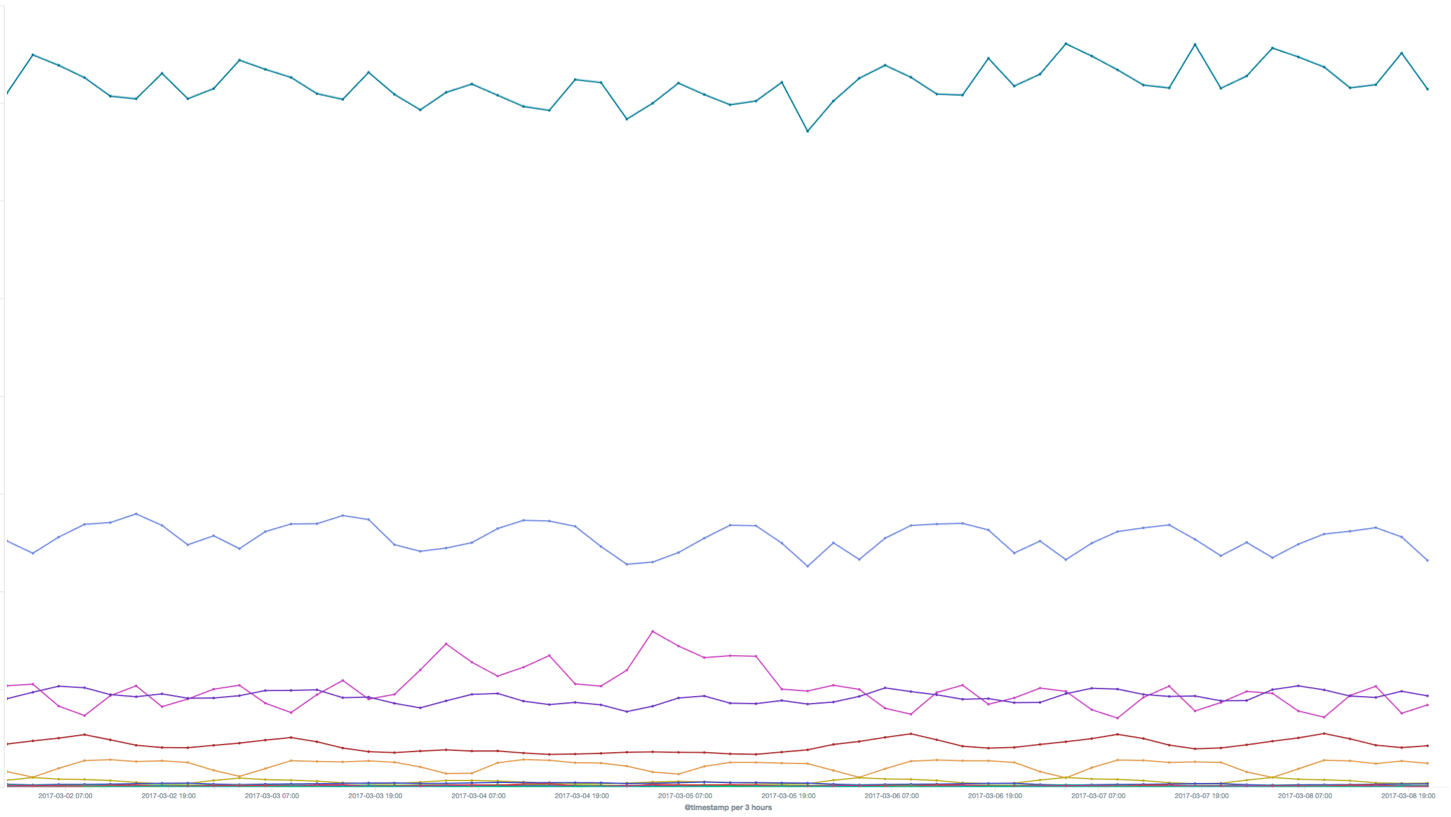

Historically, DNS has been quite stable, but nevertheless, sh!t happens. There are a few ways we monitor our DNS infrastructure. We collect metrics emitted by Unbound on our resolvers, including number of queries by record type, SERVFAILs, and net packets:

Queries per 5 minutes per resolver

We also monitor our record generation jobs for gaps or spikes:

# of A, CNAME, and PTR records generated for physical hosts and GCP instances

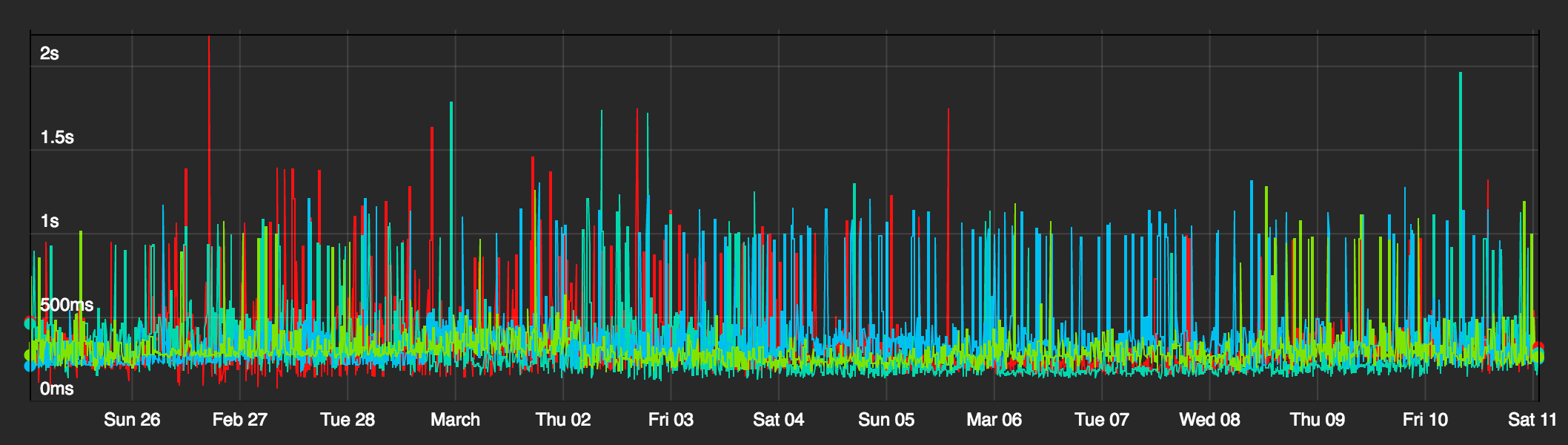

Most recently, we built a tool that allows us to track response latency, availability and correctness for particularly important records, and deployment latency. For internal latency, availability, and correctness, we use dnspython to query our resolvers and authoritative nameservers from their respective datacenter suites.

For external latency, through Pingdom’s API, we grab the response latency from our public nameservers. While Pingdom’s monitoring is very valuable to us, we’ve found it difficult to tease out from where they send their queries to measure latency, as you can see in this pretty volatile graph:

Response time per public nameserver, as reported by Pingdom

Our other DNS curiosities

Beyond its typical uses, we leverage DNS in interesting ways.

Client Error Reporting

There will always be clients that cannot connect to Spotify at all. In order to track the errors and number of users affected, and to circumvent any potentially restrictive firewalls, we introduced error reporting via DNS. The client would make a single DNS query to a specific subdomain, with all the relevant information needed in the query itself, and the queried DNS server then logs it. It’s then parsed, and tracked in this lovely Kibana graph:

Client errors by code

DHT ring

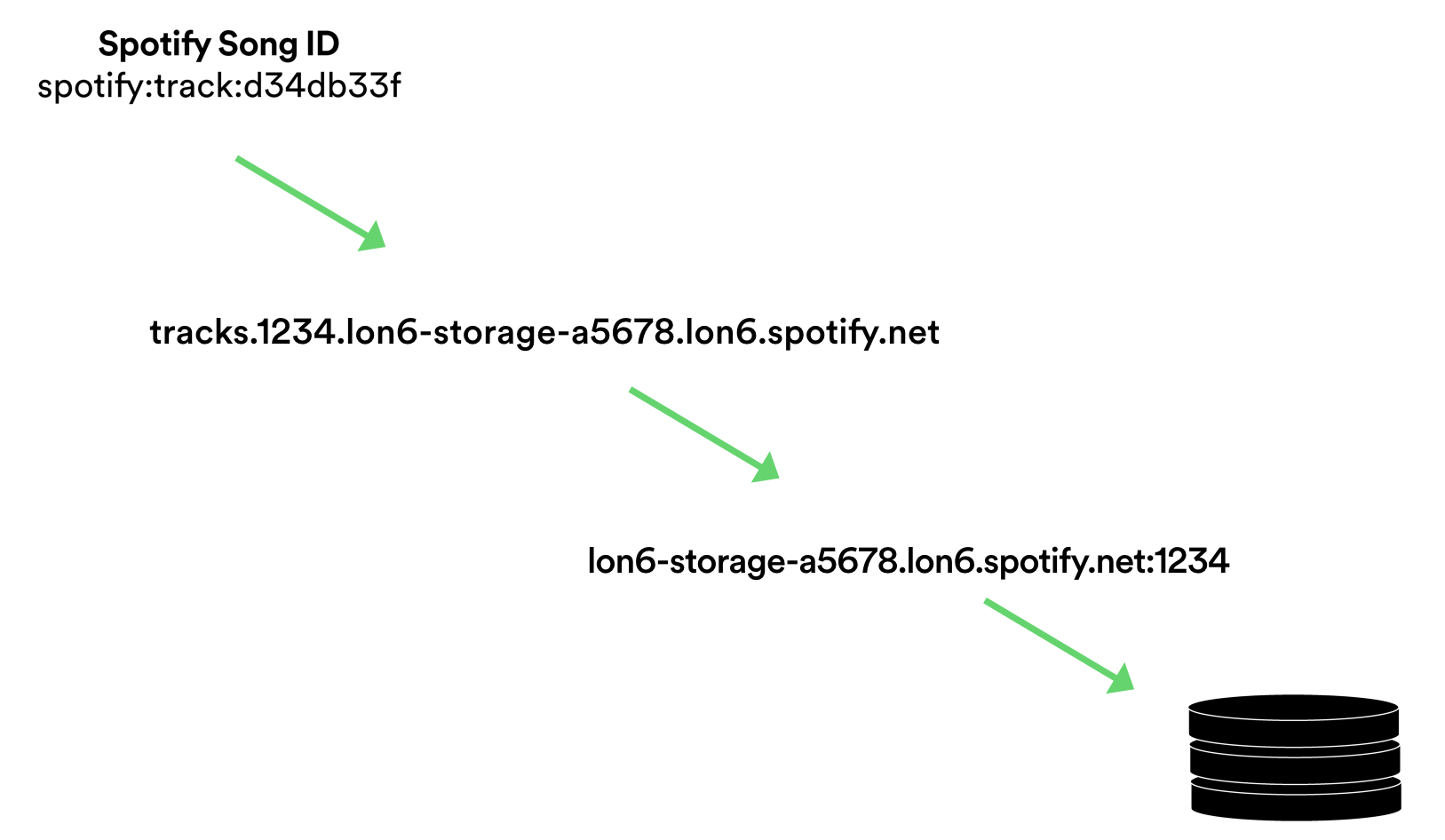

We also use DNS as a DHT ring with TXT records as storage for some service configuration data. One implementation is for song lookup when it isn’t already locally cached. When the Spotify client lookups a requested song, the song ID itself is hashed, which is a key along the ring.

The value associated with the key is essentially the host location where that song can be found. In this very simplified case, Instance E owns keys from 9e to c1. Instance E actually points to a record, something like tracks.1234.lon6-storage-a5678.lon6.spotify.net:

This isn’t a real host, however. It just directs the client to query lon6-storage-a5678.lon6.spotify.net via port 1234 in order to find the song that has the ID “d34db33f”.

Host naming conventions

Not really a DNS-specific use, but relevant nonetheless: the current convention of our hostnames contains the datacenter suite location, the role of the machine, and the pool that it’s grouped with. As mentioned in Managing Machines at Spotify, every machine typically has a single role assigned to it, where a “role” is Spotify-parlance for a microservice.

For example, we might have a machine with a hostname ash2-dnsresolver-a1337.ash2.spotify.net. The first four characters tells us that it’s in our Ashburn, Virginia location, in our second “pod” setup there. The next section, dnsresolver, tells us that the host has the role “dnsresolver” assigned to it. This allows puppet to grab the required classes and modules for that role, installing the needed software and setting up its configuration. The first character of last segment, a, is a reference to what we call a pool, and is designated by the team who owns that service. It can mean what they choose; for example, it can be used for separating testing over production, canary deploys, or directing puppet with further configuration. The number – 1337 – is a randomized bit that is unique to the individual host itself.

You might have noticed the use of .net rather than .com in the example. Spotify makes use of both spotify.com and spotify.net TLDs. Originally, .com and .net was intended for commercial and network infrastructure use, respectively (despite .net not being mentioned in the related RFC). However, that distinction has not been enforced in any meaningful way. Nevertheless, Spotify, for the most part, makes use of the original designation with .net as many internal and infrastructure-related domains, while .com for public-facing, commercial use.

Microservice Lookup

To help engineers quickly see all the machines associated for a particular role, we’ve added the automatic creation of “roles” zone files. By using the role that you’re interested in, you can dig the “roles” zone to get a list of host IPs:

$ dig +short dnsresolver.roles.ash2.spotify.net

10.1.2.3

10.4.5.6

10.7.8.9

Or with pointer records, you can get a list of their fully qualified domain names:

$ dig +short -t PTR dnsresolver.roles.ash2.spotify.net

ash2-dnsresolver-a1337.ash2.spotify.net.

ash2-dnsresolver-a0325.ash2.spotify.net.

ash2-dnsresolver-a0828.ash2.spotify.net.

What we learned along the way

Only when you entangle yourself in DNS do you realize new ways to break it, some weird intricacies, and esoteric problems. And there is certainly no better way to bring down your entire service than to mess with DNS.

Differences in Linux distributions

A few years ago, we migrated our entire fleet from Debian Squeeze to Ubuntu Trusty, including a gradual migration of our authoritative nameservers. We rolled out one at a time, testing each one before moving on to the next to ensure that it could resolve records and, for the public nameservers, receive requests on eth1.

Upon the migration of the final nameserver – you guessed it – DNS died everywhere. The culprit turned out to be a difference in firewall configuration between the two OSes: the default generated ruleset on Trusty did not allow for port 53 on the public interface. This was missed because only dnstop was used to test connections being received, but the public interface wasn’t directly queried, therefore missing rejected requests.

Issues at Scale

Truncated TCP Responses

In support of part of our data infrastructure, we have nearly 2500 hosts dedicated for Hadoop worker roles. Each host has an A record and a PTR record. When querying for all machines, because of the number of records being too large for UDP, DNS falls back to TCP.

$ dig +short @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | head -n 4

;; Truncated, retrying in TCP mode.

10.254.52.15

10.254.63.7

10.254.74.8

$ dig +tcp +short @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | wc -l

2450

However, with PTR records, we do not get the expected number back:

$ dig +tcp +short -t PTR @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | wc -l

1811

Looking at the message size:

$ dig +tcp @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net -t PTR hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | tail -n 5

;; Query time: 552 msec

;; SERVER: 10.254.35.16#53(10.254.35.16)

;; WHEN: Fri Mar 10 18:52:04 2017

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 65512

$ dig +tcp @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net -t PTR hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | tail -n 5

;; Query time: 481 msec

;; SERVER: 10.254.35.16#53(10.254.35.16)

;; WHEN: Fri Mar 10 18:52:19 2017

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 65507

$ dig +tcp @lon4-dnsauthslave-a1.lon4.spotify.net -t PTR hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net | tail -n 5

;; Query time: 496 msec

;; SERVER: 10.254.35.16#53(10.254.35.16)

;; WHEN: Fri Mar 10 18:53:13 2017

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 65529

Response sizes hover right below 65,535 bytes, the max size of a TCP packet. This certainly makes sense, but what is a bit of a head scratcher is when sending a query through one of our DNS resolvers, we get nothing back, with no sign of any errors:

$ dig +tcp @lon4-dnsresolver-a1.lon4.spotify.net -t PTR hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net

; <<>> DiG 9.8.3-P1 <<>> +tcp @lon4-dnsresolver-a1.lon4.spotify.net -t PTR hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net

; (1 server found)

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 34148

;; flags: qr tc rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;hadoopslave.roles.lon4.spotify.net. IN PTR

;; Query time: 191 msec

;; SERVER: 10.254.35.17#53(10.254.35.17)

;; WHEN: Sat Mar 11 13:38:00 2017

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 52

We partially put ourselves in this pickle with our long host naming conventions discussed earlier. But it seems as if Unbound entirely blocks responses that are larger than the maximum size of a packet, regardless of TCP or UDP (see “msg-buffer-size” in docs).

Docker Upgrades

At Spotify, we’ve been using Docker with our own orchestration tool, Helios, for a fews year now. Docker gives us the ability to ship code faster and with greater confidence, but it hasn’t always been smooth sailing.

Some of our services use host-mode networking, wherein the container has the exact same network stack as the host. When upgrading Docker from 1.6 to 1.12, we notice that requests to the host’s Unbound service were rejected. This was because when using 1.6, the source IP appears to be localhost. But with 1.12, the source IP appears as the eth0 IP of the host, and therefore is rejected by our Unbound setup. Despite this upgrade being gradually rolled out to the services using containers, it affected over half of the current active users for over an hour.

Future of DNS at Spotify

For the most part, our DNS infrastructure has been very stable and doesn’t require babysitting. But it’s certainly a lot of pressure: if we mess something up, it has the potential to impact a lot of users.

At Spotify, we’ve been focusing a lot of effort recently in the concept of ephemerality. We want our engineers to not treat hosts as pets, but as cattle. This means we want to provide our service owners the ease and ability to scale up and down as needed. But our current infrastructure prevents this.

Moving to Google DNS

You may remember that our propagation time for new DNS records is agonizingly slow. When perfectly timed, a newly spun-up host will have its relevant A and PTR records propagated to our authoritative nameservers in 15 minutes. If the staggered timing of our cron jobs were not an issue, it would be cut down to 12 minutes. But on average, new records are propagated and resolvable – and therefore able to take traffic – in 20-30 minutes. This is far from ideal when wanting to quickly scale quickly, much less so when responding to incidents requiring changes to a service’s capacity.

Before our move to Google Cloud, this issue had gone unnoticed. It takes nearly as long for our physical machines to initially boot up and install required services and packages. Yet with Google Compute, instances are up and running within minutes, exposing the latency in DNS record propagation.

As a recent hack project, we played around with Google’s Cloud DNS offering. It has not publically released its feature for automatic DNS registration upon instance launch, so we plugged the Cloud DNS’s API into our capacity management workflow. The results were pretty remarkable: new records were propagated and resolvable in less than a minute after the initial instance request, essentially improving propagation time by an order of magnitude.

So eventually, after we platformize our hack and are comfortable from having run parallel infrastructures for some time, we’ll be handing off our DNS infra to the folks that probably know how to do it better than us.

Summary

Similar with our approaches with our infrastructure, we try to tackle our problems in an iterative and engineering-based way. We first approached DNS in more of an immediate, one-off fashion: manual record management and deploys were adequate when there wasn’t much movement for our backend services or pressure to scale quickly. Then as Spotify’s infrastructure grew up, new services being developed, and more users to support, we needed an automated and hands-off strategy, which has served us well for 3 years. Now, with the focus on ephemerality, we have the opportunity to challenge and re-think our approach to Spotify’s DNS infrastructure.

If these problems interest you, we have many opportunities to join the band!