When Should I Write an Architecture Decision Record

TL;DR Have you made a significant decision that impacts how engineers write software? Write an ADR!

An Architecture Decision Record (ADR) is a document that captures a decision, including the context of how the decision was made and the consequences of adopting the decision. At Spotify, a handful of teams use ADRs to document their decisions. One of these teams, The Creator Team, focuses on providing tools for creators to express themselves on Spotify, as well as access data about their content. The Creator Team utilizes ADRs to document decisions made related to system design and engineering best practices. We typically arrive at these decisions through discussion in Request for Comments (RFCs) or during our engineering meetings.

What are the benefits?

Since adopting ADRs, the team observed many benefits, some of which include:

Onboarding

Future team members are able to read a history of decisions and quickly get up to speed on how and why a decision is made, and the impact of that decision. For example, in 2019 the Creator web engineers decided to adopt React Hooks. We came to this decision during one of our bi-weekly web engineering meetings and after running a small experiment in a small part of our application. The consequence of this decision? We stopped creating new class components in favor of function components.

Ownership Handover

At Spotify, we work in an agile environment where we aim to learn fast. In this environment, we do not hesitate to implement organizational change to meet the needs of our users as it evolves. When our organization changes, we sometimes have to move ownership of systems from one team to another. In the past, a lot of context/knowledge was lost when this took place, triggering a decrease in productivity. This problem has become less severe with the introduction of ADRs. New owners of a system can quickly get up to speed with how and why the system’s architecture evolved in the way it did simply by reading through the ADRs.

Alignment

ADRs have made it easier for teams to align on best practices across Spotify. Alignment has the benefit of removing duplicative efforts, making code reusable across projects, and reducing the variance of solutions that central teams need to support. For example, teams in the Stockholm office were able to read, reference, and adopt the “React Hooks” ADR New York-based Creator web engineers wrote.

Ok I’m in! But when should I write one?

So you might be thinking, “ADRs sound great! It’s exactly what my team needs to facilitate decision-making while keeping a log of decisions for future teammates, as well as our future selves! But when should I write one?“

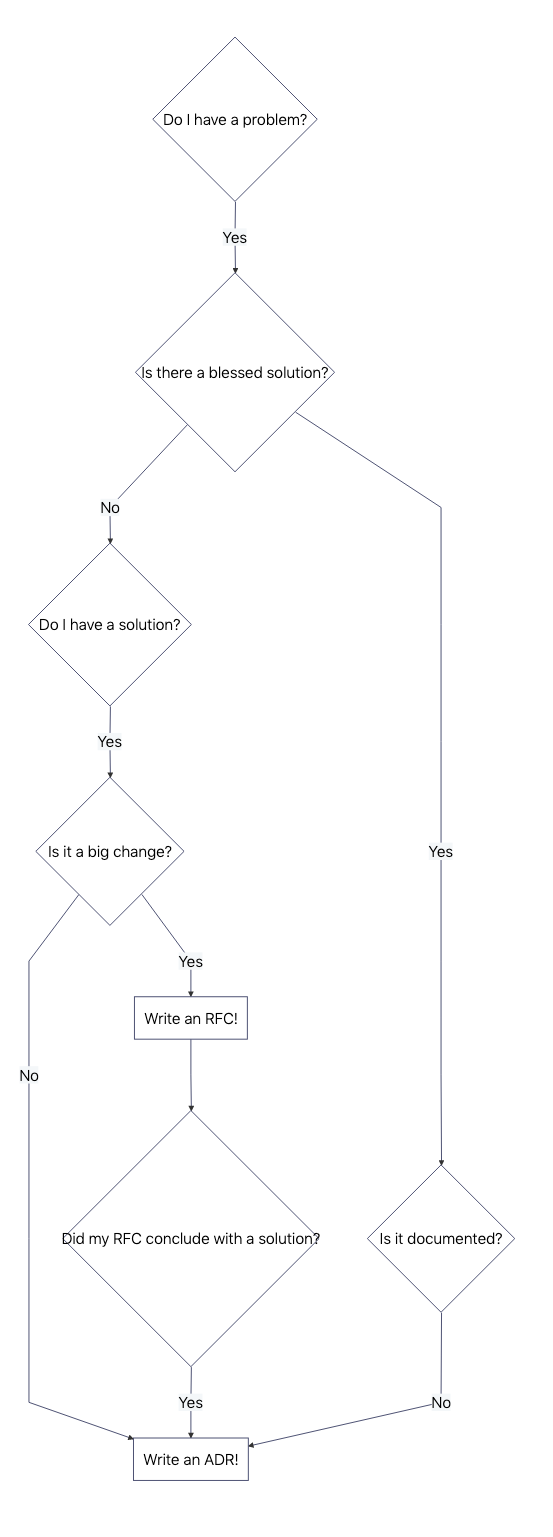

An ADR should be written whenever a decision of significant impact is made; it is up to each team to align on what defines a significant impact. To get you started, below are a few scenarios with my mental model for determining when to write an ADR:

Backfilling decisions

Sometimes a decision was made, or an implicit standard forms naturally on its own, but because it was never documented, it’s not clear to everyone (especially new hires) that this decision exists. If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? Similarly, if a decision was made but it was never recorded, can it be a standard? One way to identify an undocumented decision is during Peer Review. The introduction of a competing code pattern or library could lead the reviewer to discover an undocumented decision. Below is my mental model for when to backfill an architecture decision:

Do I have a problem? Yes

Is there a blessed solution? Yes

Is it documented? No

Write an ADR!

Proposing large changes

Over the lifecycle of a system, you will have to make decisions that have a large impact on how it is designed, maintained, extended, and more. As requirements evolve, you may need to introduce a breaking change to your API, which would require a migration from your consumers. We have system design reviews, architecture reviews, and RFCs to facilitate agreements on an approach or implementation. When these processes run their course, how should we capture the decisions made? Below is my mental model for how to document these large changes:

Do I have a problem? Yes

Is there a blessed solution? No

Do I have a solution? Yes

Is it a big change? Yes

Write an RFC!

Did my RFC conclude with a solution? Yes

Write an ADR!

Proposing small/no changes

In our day-to-day, we make small decisions that have little to no impact. The cost of undocumented decisions is hard to measure, but the effects usually include duplicated efforts (other engineers try to solve the same problems) or competing solutions (two third-party libraries that do the same thing). Enough small decisions can compound into a future problem that requires a large process or effort (ie. migration). Documenting these decisions doesn’t have to cost much. ADRs can be lightweight. Below is my mental model for working through this:

Do I have a problem? Yes

Is there a blessed solution? No

Do I have a solution? Yes

Is it a big change? No

Write an ADR!

Let’s roll it up into a diagram!

When should I write an Architecture Decision Record? Almost always!